How the British came up with Indian time. How the British came up with Indian time. How the British came up with Indian time. How the British came up with Indian time. How the British came up with Indian time

How the British came up with Indian time. How the British came up with Indian time. How the British came up with Indian time. How the British came up with Indian time

12 June 2018

How the British came up with Indian time

The original 24 time zones, intended to divide the globe into equal parts, were almost immediately altered to suit the needs of this or that country. First to take liberties with time were the British, with an eye on their numerous colonies.

How we organise time takes root in the movements of the stars – which define our days, months and years – and certain man-made conventions, time zones being one of them. Established in 1884, they are a reminder that while nature tends to know what she's doing, the same cannot always be said of we humans. Almost from the moment time zones were introduced, we've been "messing around with meridians" to suit our geographic, political or trading agendas. Or for more down-to-earth reasons. The half-hour added to India's time zone is a case in point. British humour, perhaps?

Keeping track

Until the late 1800s, there were potentially as many local times as places on Earth, each based on the movement of the Sun (true solar time). North America had more than seventy local times, Europe close to thirty. The railroad - which arrived in the United States circa 1812 and slightly later, around 1825, in Europe - combined with the newly invented telegraph system would put an end to this patchwork of local times. As towns then nations increasingly communicated with each other, the need for a single uniform time became clear.

Crown up, a pocket watch showed British time. Crown down, it showed Indian time.

In 1847, the British Railway Clearing House recommended that all British railway companies base their schedules on the time at Greenwich Observatory (already used by navigators to plot their position at sea). In 1883, their North American and Canadian counterparts agreed to divide their territory into five equal zones, simultaneously introducing the novel notion of "time zones". A year later, delegates at the International Meridian Conference in Washington voted a resolution to divide the globe into 24 zones of one hour each, with Greenwich as the prime meridian. It wasn't long before this new system had been adopted by the vast majority of countries. In theory at least.

Every minute counts

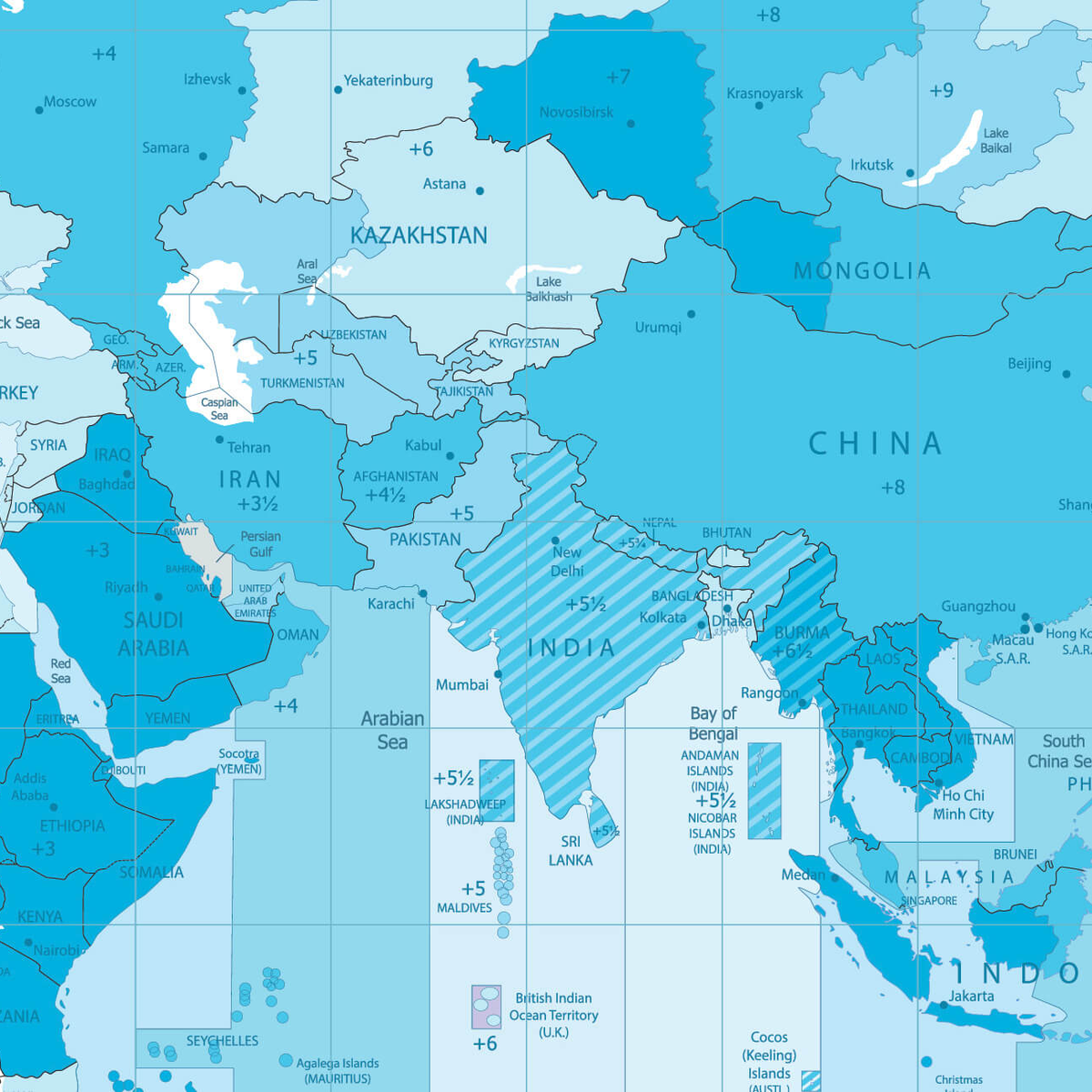

Theoretically then, the area covered by a single time zone should represent one hour and one hour only. But things don't always go to plan... Certain of the largest nations, beginning with China, extended across several zones but wanted a single time for the entire country. Others refused to share the same time as a neighbouring enemy by taking a half or even a quarter of a zone. Nepal, for example, is offset from Greenwich by +06:45. Others still have switched zones to align with trading partners. All of which explains why there are no longer 24 time zones running in a straight line from Pole to Pole but 37 whose contours are enough to convince us that time is a relative concept.

The British were probably the first to play around with time, a consequence of the country's expansionist policy. Well before the advent of universal time measured from Greenwich, Great Britain instated legal times in its colonies. India, for example, has had its own time since 1802, following the creation in 1792 by the East India Company of the Madras Observatory. Logically, India's time should have been offset by five hours from the time observed in Greenwich. In reality, it became +05:30. Why? Because the ever-practical Brits realised that when a pocket watch was turned with its crown on the bottom, it would show the time in India. If it was 10.30am in London, it was 4pm in New Delhi. At 3pm it was 8.30pm. Elementary...