Marine resources: pillage or protection?. Marine resources: pillage or protection?. Marine resources: pillage or protection?. Marine resources: pillage or protection?. Marine resources: pillage or protection?

Marine resources: pillage or protection?. Marine resources: pillage or protection?. Marine resources: pillage or protection?. Marine resources: pillage or protection?

17 November 2022

Marine resources: pillage or protection?

Forum, Sustainability

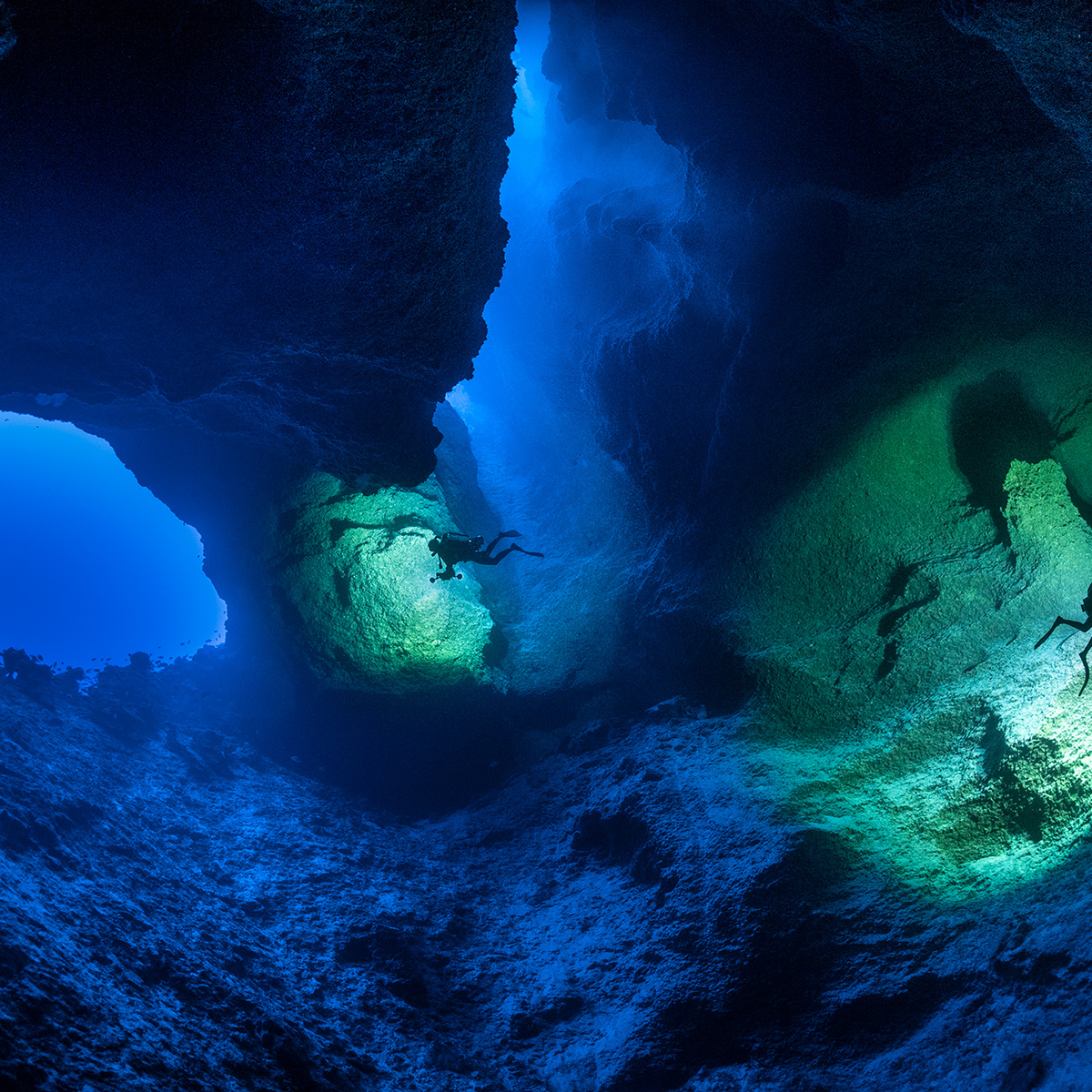

Rich in minerals and diamonds, the seabed has become a target for commercial exploitation without any true understanding of the consequences on marine ecosystems. Marine diamond mining has already started and nations such as the Republic of Nauru are eager to harness their mineral resources.

When Jules Verne wrote his 1869 novel Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, he made numerous predictions as to the treasures beneath the ocean’s surface. These treasures do exist: not as the wonders observed from the Nautilus but as mineral wealth many would love to harvest. Indeed, the seabed contains vast quantities of the strategic materials required to manufacture high-tech products, as well as lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicles, photovoltaic cells and wind turbines; all essential in the transition to a low carbon economy.

Three types of mineral deposits of commercial interest occur below 400 to 6,000 metres. They are polymetallic nodules which contain metals including iron, manganese, copper, cobalt and nickel; cobalt crusts which, as well as cobalt, contain precious metals including platinum and rare metals such as zirconium; and sulphide deposits that are rich in zinc, copper, gold, silver and rare metals. The seabed is also a source of diamonds which are brought to the surface by volcanic eruptions. Erosion causes these diamonds to then break away from the rock and be dispersed, forming secondary deposits known as stream placers. When river currents are strong enough to carry the diamonds into the ocean, they form marine placers.

The economic advantages of deep seabed mining must be shared “for the benefit of mankind as a whole”.

Exponential needs

Can these natural resources satisfy our seemingly endless demand for raw materials? Olivier Vidal, a researcher at France’s National Institute for Earth Sciences and Astronomy (CNRS/INSU), does the math in his book, Matières premières et énergie ; les enjeux de demain. He explains how a 3% annual increase in metal production, currently the case for copper and iron, will result in a doubling of production every twenty years. If consumption continues at the present rate, the OECD Global Material Resources Outlook to 2060 report projects that global materials use will more than double from 85 gigatonnes to 180 gigatonnes in 2060, as the global population increases by 2.5 billion.

France advocates a precautionary ban on deep-sea mining

The looming possibility that we should run out of materials, and the colossal investments required for terrestrial mining, explain growing interest in the resources that lie on the seabed. However, most deep-sea minerals are located in exclusive economic zones (EEZ), which are areas of the sea in which coastal nations can exercise their exploitation rights over natural resources. This is where the International Seabed Authority (ISA) comes into play. The exploitation of minerals on the seabed was first addressed in 1982 during negotiations that led to the formation of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, which entered into force in 1994. That was also the year the ISA came into being. The Convention introduced the concept of the Area: the seabed and subsoil beyond the limits of national jurisdiction, which comprises just over half the total seabed. The International Seabed Authority and its 168 members are mandated under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea to regulate exploration for and exploitation of deep seabed minerals in the Area.

Debmarine’s Benguela Gem is described as the world’s most technologically advanced marine diamond recovery vessel

The ISA is currently focused on the development of a regulatory regime for exploitation of these resources. Michael Lodge is Secretary-General of the International Seabed Authority. He explains how, as a regulatory body, the ISA’s primary concern is to balance the societal benefits of deep seabed mining, such as access to essential minerals, the nondisplacement of communities, extensive deep sea research and technological development, against the need to protect the marine environment. These resources, he says, must be developed “for the benefit of mankind as a whole.” The economic advantages of deep seabed mining will most likely be shared in the form of royalties paid to the ISA, with particular emphasis on the developing countries that do not have the technology and capital to carry out seabed mining for themselves.

Environmental impacts

What about the inevitable environmental consequences of deep seabed mining? “The fact that no part of the Area may be exploited without permission from the Authority ensures that the environmental impacts of deep seabed mining will be monitored and controlled by an international body,” says Michael Lodge. “It is evident, nevertheless, that mining will impact the marine environment to some extent, especially in the immediate vicinity of mining operations. Impacts may include the crushing of living organisms, the removal of substrate habitat and the creation of sediment plumes. There is also the possibility of other environmental damage through malfunctions in the riser and transportation system, hydraulic leaks, and noise and light pollution.”

Thus far the International Seabed Authority has issued 31 exploratory contracts (not mining contracts) to 22 countries. However, not everyone is prepared to wait. Nauru, a republic of Micronesia, is sponsoring a subsidiary of The Metals Company, a Canadian mining company. While ISA’s work so far has been to require exploration contractors to conduct scientific research into the potential long-term impacts of deep-sea mining, in 2021 Nauru triggered a provision of the Convention of the Law of the Sea which requires the Authority to finalise deep-sea mining regulations within two years. If it fails to do so, Nauru will probably begin mining in the summer of 2023 with no regulations in place.

At the same time as the ISA was holding an assembly at its headquarters in Kingston, Jamaica, early November, nations were meeting at COP27 in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt. In his opening address, President Emmanuel Macron clarified France’s position on the subject: “France supports the ban on deep-sea mining. The ocean, like space, must be a new frontier for cooperation and multilateralism. We must do all that we can to preserve the ocean from the point of view of climate and biodiversity.” France joins Germany, Chile, Costa Rica, Spain, New Zealand, Panama and several Pacific island nations, all of which support a precautionary moratorium on deep-sea mining until scientific data enables a full understanding of these largely unknown ecosystems.

The mysteries of the deep

The ISA has awarded exploratory contracts over 1.3 million square kilometres of the high seas, warns the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition, an alliance of some one hundred conservation organisations. If mining is allowed to proceed, this would be the biggest mining operation ever in history… with the risks this implies for the ocean’s ecosystems and species, two-thirds of which remain unidentified. “The abyssal plains lie some 5,000 kilometres from the surface. These are extreme environments where no light penetrates,” writes Lénaick Ménot, a researcher at the Deep Environment Laboratory at Ifremer (France’s national institute for ocean science) on polytechnique-insights.com. “The water temperature is about 2°C and the pressure is high. Contrary to all expectations, a great diversity of species can be found there. However, many of them have only a small number of individuals because food is scarce: only 1% of the organic matter produced on the surface reaches the deep sea. Fish, crustaceans, sea cucumbers, starfish, sea urchins and marine worms live there. How can this great diversity be explained? This remains a mystery today.”

The implicit question is, can we mine the seabed in a way that is environmentally acceptable and economically feasible, given the huge technological investments required to work at this depth? Debmarine Namibia, a joint venture owned equally by De Beers Group and the Government of the Republic of Namibia, already has its answer. The company has been prospecting for and retrieving marine diamonds off the Namibian coast since 2002, dredging at 90 to 150 metres below sea level. While this doesn’t qualify as deep-sea mining it does raise identical issues, with the exception that Debmarine does not need the International Seabed Authority’s approval to operate in Namibia’s territorial waters.

Debmarine’s newest vessel, the Benguela Gem, gives the best answer to the question of the economic profitability of marine diamond mining. Described as the world’s most technologically advanced marine diamond recovery vessel, it measures 177 metres long and cost Debmarine US$ 420 million. It joins the existing fleet of seven vessels and will add 500,000 carats of high-value diamonds to Debmarine’s annual production. This is an increase of around 45% on the 1.1 million carats of marine diamonds extracted in 2021. “The company operates in an area that benefits from the Orange River’s alluvions. Diamonds are carried into the delta and its sediments,” says Cédric Berruex, a former director at Piaget and founder of the Edelmont jewellery company. “This is a unique situation. The diamonds extracted in this area are of the highest quality. As a secondary deposit, leaving aside environmental problems, this coastal site is a windfall for Debmarine at a time when the mines in the Namibian desert are becoming depleted after decades of production.”

From Namibia to Greenland

Jan Nel, Operations Manager at Debmarine, confirms this view: “This is the richest known marine diamond deposit in the world,” he told AFP reporters aboard the Mafuta, another of the company’s vessels. “There is fifty years’ work there.” This is music to the ears of a company such as De Beers, as a diversification from land-based operations. “These operations generate considerably less pollution than the exploitation of primary deposits, the giant open craters where tonnes of ore are crushed amidst the endless toing-and-froing of heavy machinery,” comments consultant Charles Chaussepied, a former director at Piaget and former chair of the Responsible Jewellery Council. “In comparison, marine mining consumes less energy and works on the surface. Obviously it raises environmental problems, as do fishing trawlers that drag nets across the seabed.”

Debmarine underlines the Benguela Gem’s state-of-the-art capacities, for example its dynamic positioning system which automatically optimises the vessel’s performance to minimise energy use. It also generates its own fresh water through heat recovery systems and a reverse osmosis plant. This leaves the question of the vessel’s inevitable impact on marine ecosystems. Debmarine promises that it is using independent scientific studies to mitigate its impact and rehabilitate damaged environments. At the time the commissioning of the Benguela Gem was announced, Debmarine had mined 8 square kilometres and extracted 5 million carats… a compelling incentive to find out whether the sea is equally “productive” elsewhere. In the waters off Greenland, for example, where De Beers has already commissioned a survey of the ocean floor. Unless a moratorium is established, prior to conclusive and independent scientific studies to determine the irremediable environmental damage caused by this “treasure hunt”.