For the watch industry, huge challenges remain. It will require buy-in from large actors in the space to shore up not just definitions, but practices, and to convince buyers to value recycled and circular luxury as highly as what went before.

There are signs. In the jewellery sector, often a forerunner for watchmaking, Prada and Pandora are now offering 100 per cent recycled gold in their products (although consumers can be forgiven for continuing to question what that means). Last July, Signet Jewelers, the world's largest retailer of diamond jewelry, announced it would be moving away from the term “recycled” and replacing it with “repurposed”. In the UK, the Royal Mint, which makes the country’s coins, said it would be using the term “recovered” to account for the ambiguity in the current definitions of recycled.

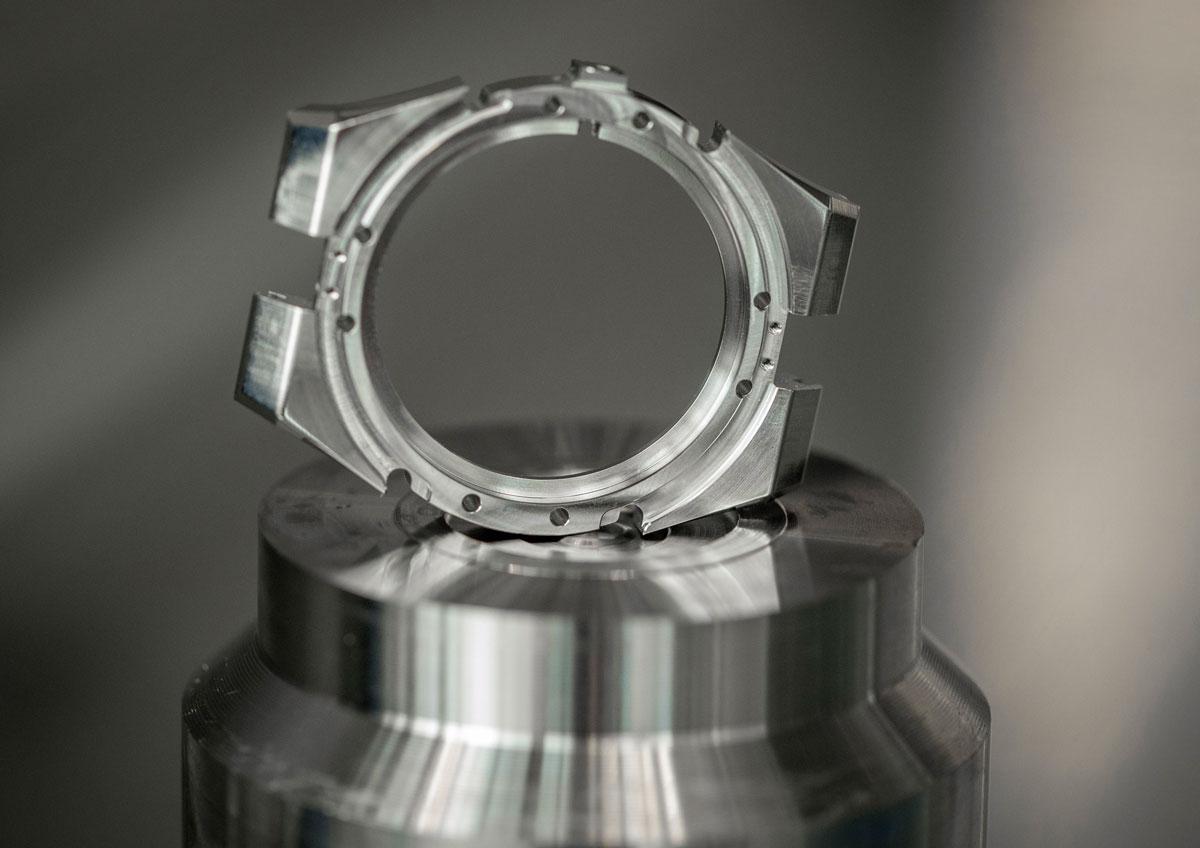

Panatere’s Broye is bullish about the future. “Brands are very interested in the circular economy and recycling,” he says. “Demand far exceeds our current production capacity. The major brands are well aware of the geopolitical stakes involved in sourcing raw materials. And the needs of the dual transition to energy and digital technology will lead to an explosion in demand for materials such as copper, lithium and nickel. New regulations on the use of critical materials will change industrial processes.”

Karib says it’s on the brands to take the lead “Groups and brands will have to pay a premium for responsible gold,” she says. “But they’re scared because they don’t want to have to reinvent the narrative. But the margins are so crazy in this industry they should be able to pay a premium for the material.”

She urges perspective. “The point is luxury is useless,” she says. “So is it acceptable that something useless is targeting increased sales without properly addressing the social impact and environmental challenges?”

It’s a question the watch industry will have to answer soon enough.