The origins of time

A history of time measurement. A history of time measurement. A history of time measurement. A history of time measurement. A history of time measurement

A history of time measurement. A history of time measurement. A history of time measurement. A history of time measurement

A history of time measurement

by Christophe Roulet

Time, the ever-elusive concept that has captivated us for centuries. Join us as we take a captivating journey through the milestones that shaped the way we measure time, from the primitive shadows of our ancestors to the precise and sophisticated timepieces that adorn our wrists today.

Meet outside your cave at 10?

When our hominid predecessors arranged to meet, did they plant a stick in the ground and use the shadow it cast to know roughly when to rock up and see their pals? Highly unlikely… though not so farfetched if we move forward in time to Homo sapiens. He’s the one whose cogitations convinced him that as well as moving through space, we also move through time. Elementary, my dear Homo sapiens, or at least from our point of view. For our hunter-gatherer, however, more concerned with the distance separating him from that herd of mammoths, such a realisation required a considerable mental effort. These early humans became conscious of passing time through their observations of regularly recurring natural events: day and night, the seasons, the path of the Sun and Moon across the sky… enough to comprehend time as a succession of yesterdays, todays and tomorrows, and build on past experiences to better anticipate the future. For a population with “no fixed abode”, this was an important evolution.

Potato-planting time

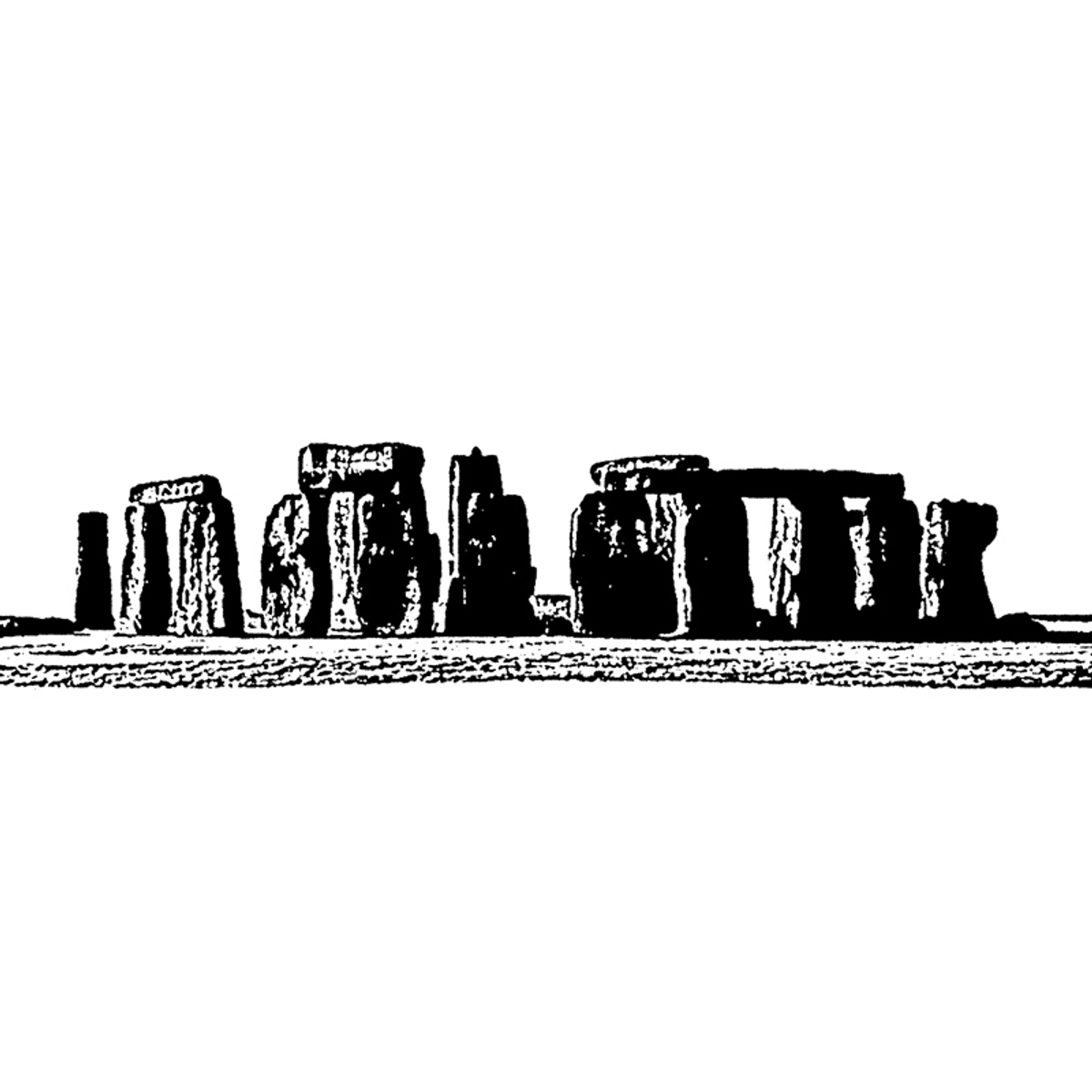

The Neolithic

Having observed these natural cycles, regular dates in the celestial agenda, our ancestors concluded that great powers were at work. Powers that warranted rituals to appease them and constructions to honour them. Menhirs and dolmens, monumental structures worthy of such a force, sprang up across Europe and North Africa from the Neolithic (10,000-2,200 BCE). Burial sites, these alignments of more or less roughly hewn stones are also testament to early astronomical observations and specifically observations of the Sun and Moon. This information was essential for knowing when to plant crops or move livestock based on the solstices, for example, or for tracking lunar months. Just one small thing was missing to go from a “simple” architectural arrangement to a more advanced conceptualisation of time in the form of calendars, hence divisions of time. That small thing was a writing system!

Aristotle said so

Antiquity

Appearing circa 4,200 BCE in Mesopotamia, as well as in China and Mesoamerica a thousand years later, writing made possible the first charts based on the apparent motions of the Sun and Moon. Better still, around 2,400 BCE the Mesopotamians imagined a unit that measured both time and distance; the basis of our sexagesimal (base-60) system of degrees of arc and minutes. Having learned to count the days, Man began to count the hours using sundials, fire clocks or clepsydras. As astronomy progressed, calendars became more precise and it wasn’t long before the information they gave was reproduced in mechanisms, as Aristotle (fourth century BCE) notes in his writings. Antikythera, anyone? Divers working off the coast of this small Greek island in the Aegean Sea discovered a shipwreck. Among the artefacts recovered from it were the remains of what became known as the Antikythera mechanism: the first known gear-driven astronomical calculator, dated to around the second century BCE. The astrolabe, an instrument used to observe and calculate astronomical positions, dates from the same period and remained in widespread use until the nineteenth century.

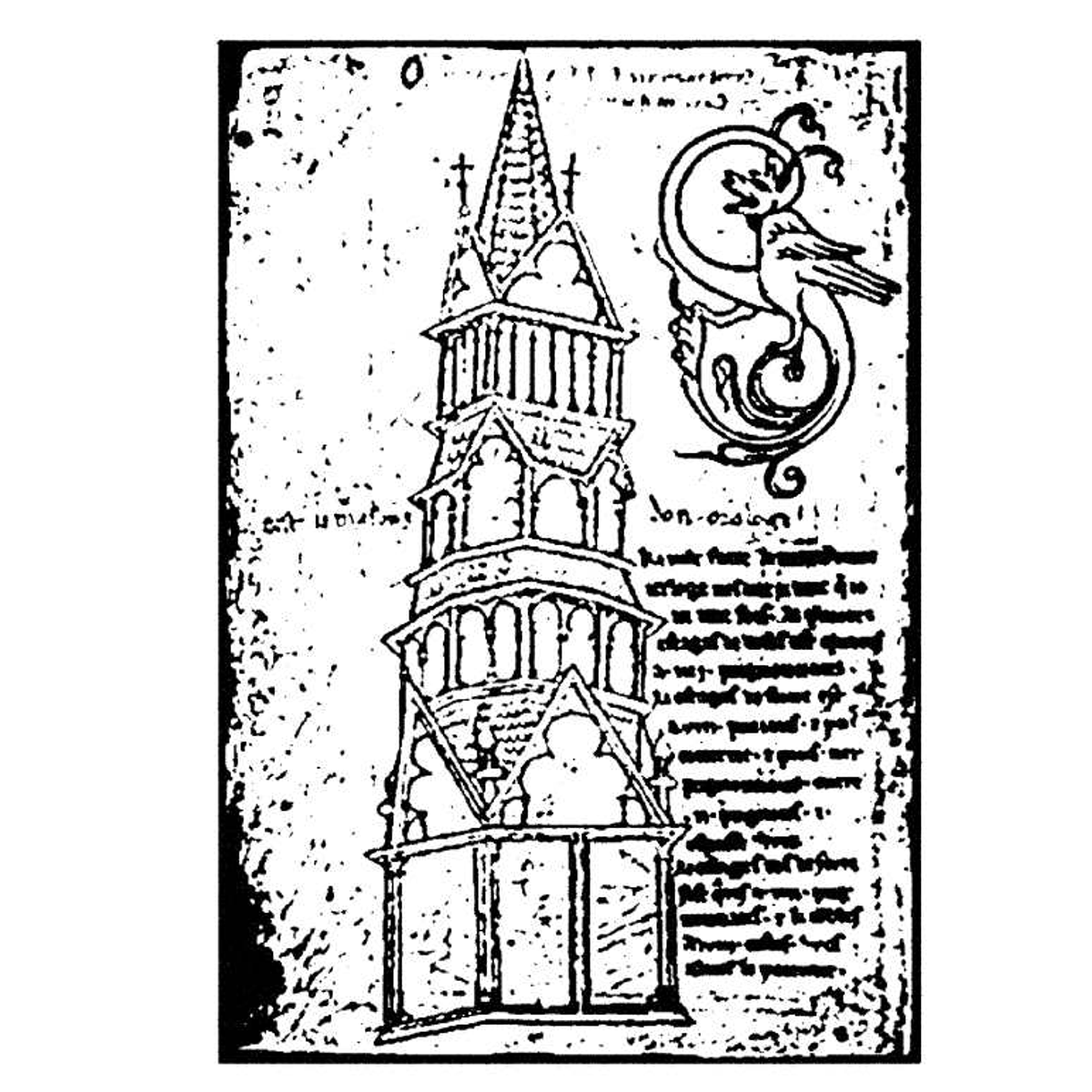

Let there be clocks

Late Middle Ages

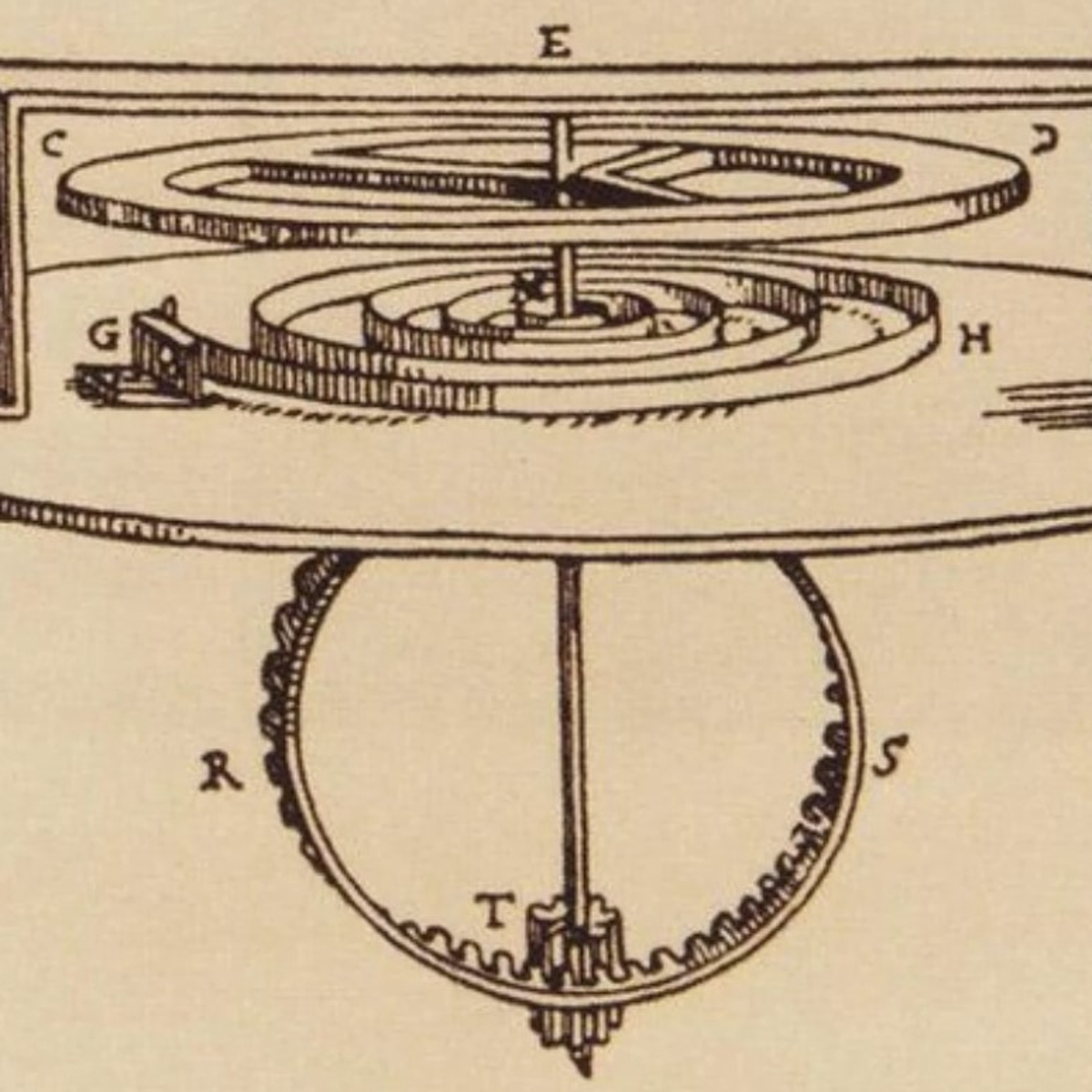

After the intellectual effervescence of Ancient Greece, time, or rather advances in how to divide and measure it, stood still. The next decisive events would occur only in the Late Middle Ages. Monks set about translating scientific texts into Latin. Nobles followed scientific progress with great interest, particularly machines (and what better example than those of Leonardo da Vinci?).

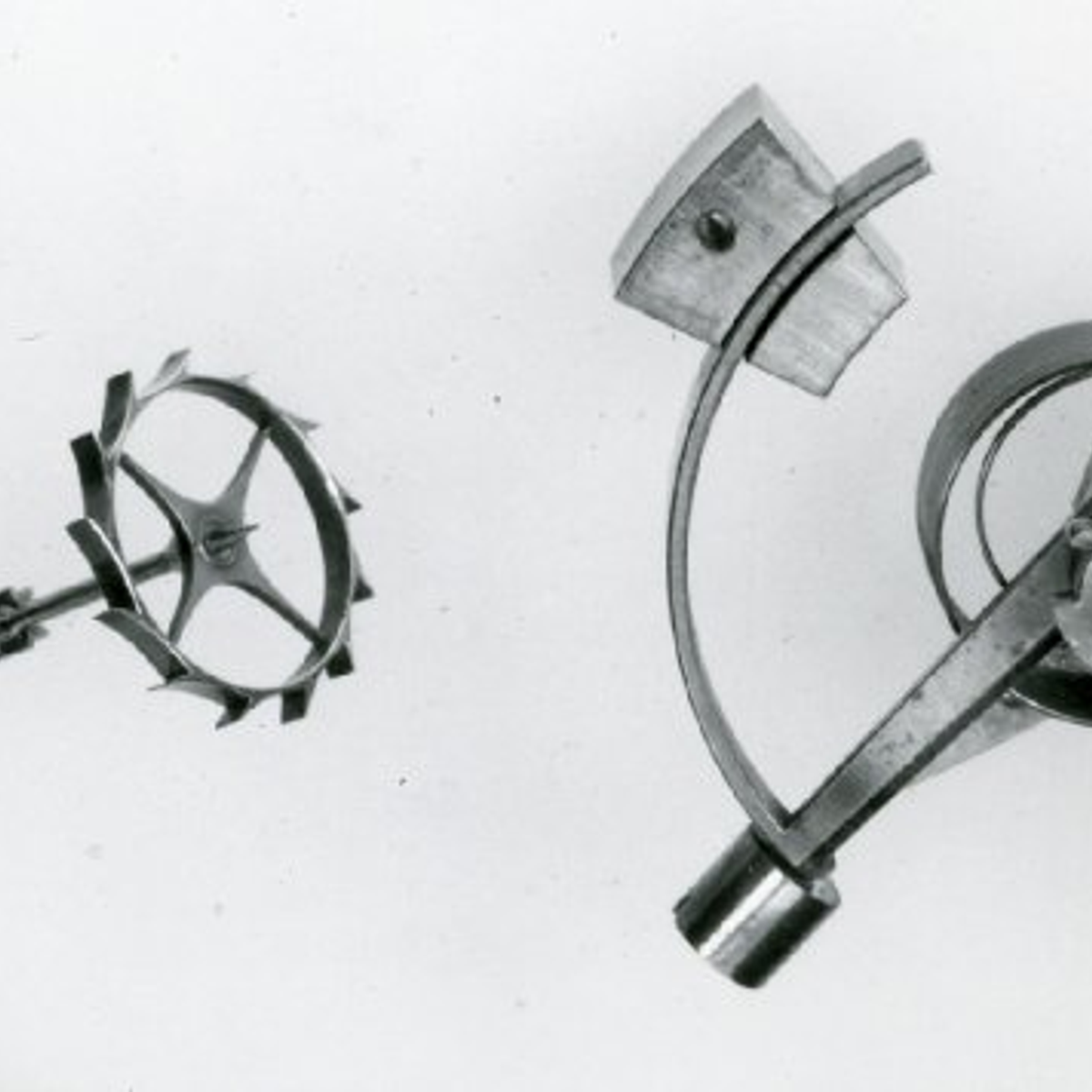

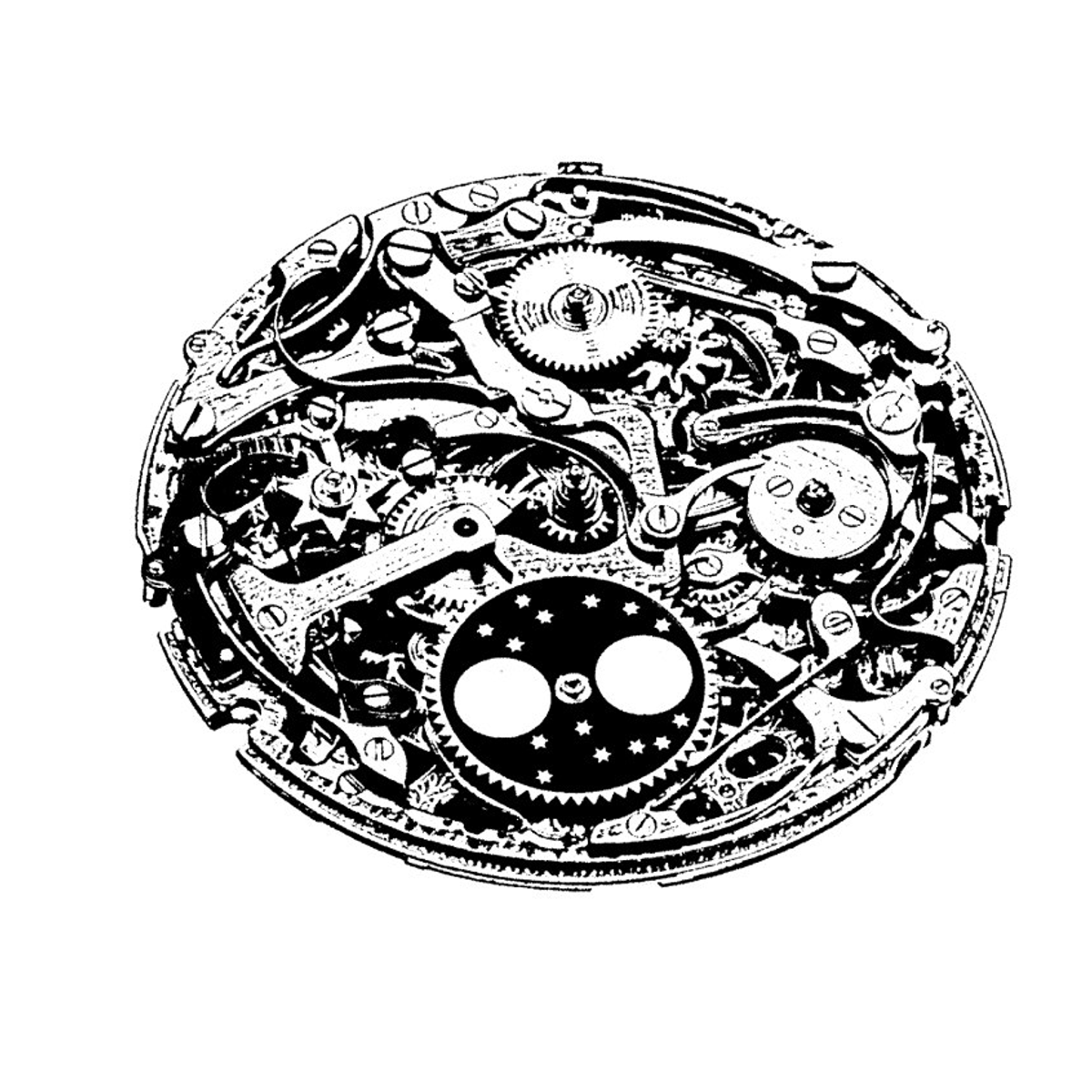

The context was ripe for the first mechanical clocks. Their principle - gears regulated by an escapement – hasn’t changed one iota, except the escapement is now driven by a spring rather than a weight. Of all the triumphs of human ingenuity, the clock has probably had the greatest influence on how we think and behave. No more need for scholarly observations; time flows like a river we have dammed; a linear progression freed from Nature’s cycles and an essential component of living together, better.

All for show

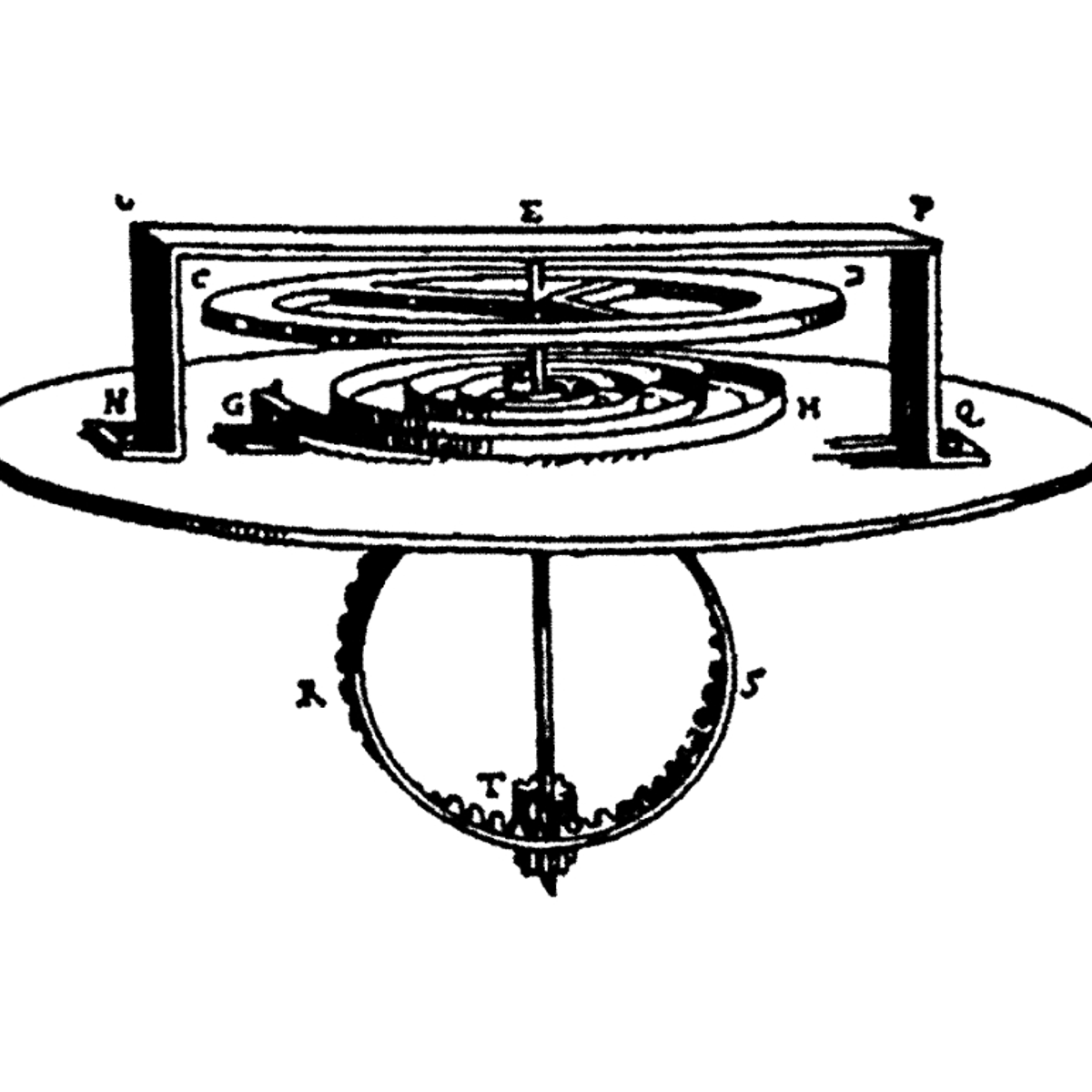

16th to 17th centuries

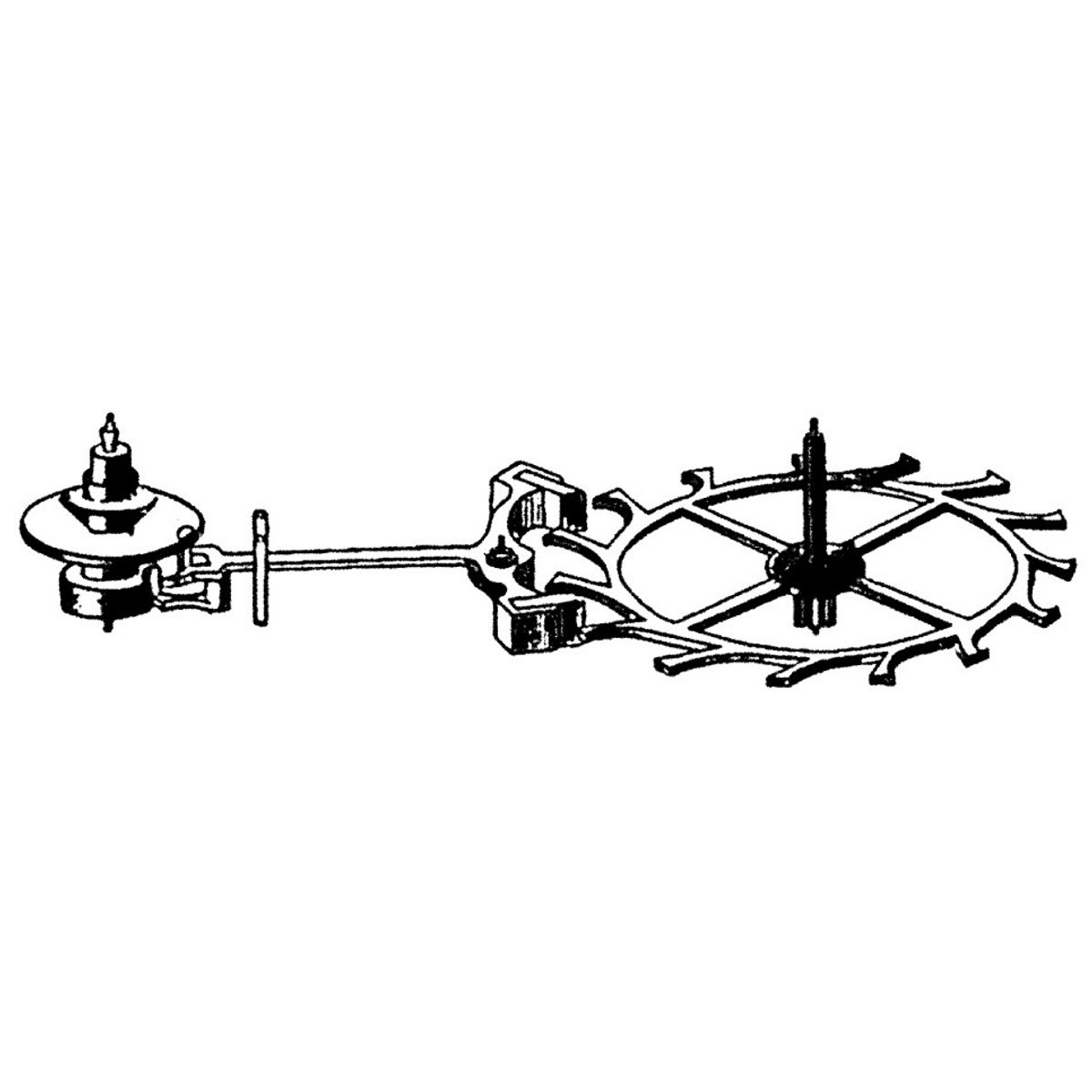

Symbols of power and progress, from their tower perch, clocks set the pace of life in town and country to the peal of bells. Soon these monumental mechanisms were being miniaturised to please a wealthy few and their desire to possess an object of great beauty that would also give them the hour. Thanks to progress in metallurgy and continued advances in science, the clock took a seat at the table then, in the late fifteenth century, shrank again to become a watch.

These timepieces were notoriously imprecise but appearances were far more important! When you arrive carrying a lavishly ornamented watch, no-one will notice you are more than two hours late. Made for show, watches were hung from necklaces, mounted in rings, set in the hilt of a dagger or attached to a wristlet and gifted to the Queen of England, Elizabeth I.

A sea change

17th to 18th centuries

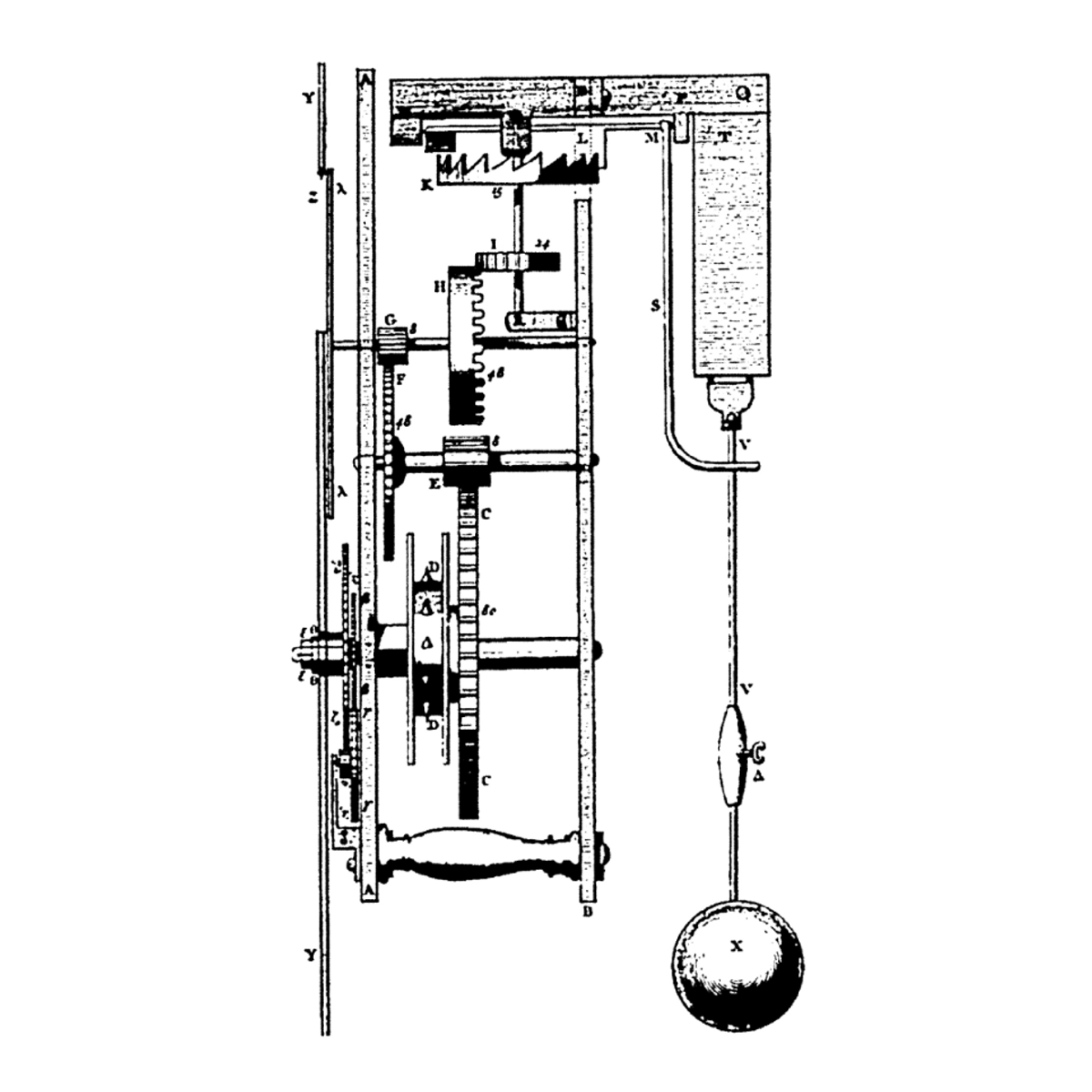

Enough frivolity! From the seventeenth century, time became a serious business. The likes of Galileo (heliocentrism), Huygens (the balance spring), Fatio (pierced jewels) and Bürgi (the second as a unit of time), to name just some, gave decisive impetus to the measurement of time. Thanks to such fundamental inventions, the reliability and precision of timekeepers advanced in leaps and bounds.

The Navy had its role to play, too. In the eighteenth century, a time of rivalry on the high seas as nations vied to take command of maritime trading routes, the inability to calculate longitude at sea - impossible without an accurate chronometer - had already cost the lives of thousands of sailors. In France and England, watchmaking’s most brilliant minds worked to resolve the problem, in some instances prompting wild accusations of “industrial espionage”. Still, precision is one thing, complications are another that would keep watchmakers busy for centuries to come.

Watches for all

19th century

From sea to land, where the latest invention was catching on fast: the steam engine. Initially intended for transportation, this modern wonder would have a double impact on late nineteenth-century societies. Steam power transformed production and sparked the Industrial Revolution. It also prompted the development of the railway, which dramatically changed lives and challenged perceptions of time as being specific to a community.

This was an era of rationalisation, including in watch production. Clocks and watches became industrial goods, manufactured in series, affordably priced and better quality thanks to interchangeable parts. Swiss makers vied with American manufacturers in this new mass market. Meanwhile, as more people travelled, and travelled further, local times were replaced by universal time measured across 24 time zones.

Anything that could be measured, a watch was expected to display by the sole means of its mechanisms. Watchmakers obliged with the creation of extraordinarily complex “grand complication” timepieces. However, after the Industrial Revolution, another revolution was about to take place that would transport the watch from pocket to wrist.

From Everest to the Mariana Trench

First half of the 20th century

A watch had always been a pocket watch… until a new leisure society - playing sport, driving cars and travelling - along with changing dress styles saw timepieces make their first timid appearances on the wrist (from around 1875). Fashionable women were first to adopt what was considered a frivolous trend, although the practicality of having the time so readily available would become apparent to soldiers in the First World War. The wristwatch’s appeal grew along with its precision, now virtually equal to that of a pocket watch. In fact the wristwatch would follow the same path as its pocket-sized cousin, becoming smaller, more practical and offering new functions designed to assist its wearer in his or her busy life. Sport, underwater exploration and aviation would play a major role in popularising the wristwatch during the first half of the twentieth century. More precise, more reliable, more robust, the wristwatch was preparing to scale the highest summits, plunge into the deepest abysses and fly across oceans.

Death by quartz?

Second half of the 20th century

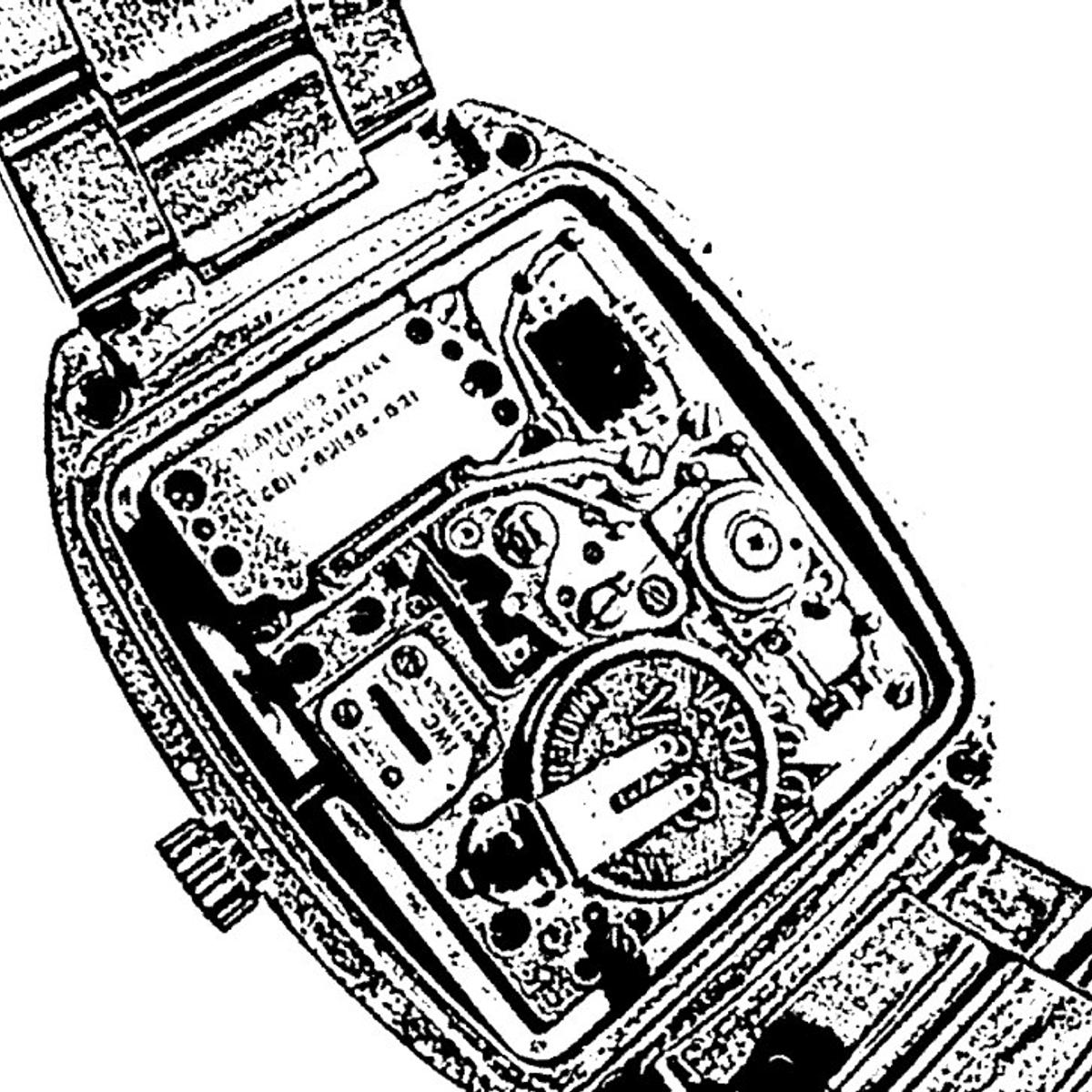

As of the 1950s, watchmakers began to explore new means of expression, turning away from the traditional mechanical movement in favour of alternative power sources, in particular electrical. In the space of two decades, after centuries of loyal service, the spiral balance spring was replaced by a tuning fork then by a quartz crystal in a prelude to the electronic watches that would flood the market from the early 1970s.

Swiss brands had perfect command of this new technology but, coming late to the party, were overwhelmed by an onslaught of modern, ultra-precise watches from Asia, offering a myriad features at mass-production prices. Meanwhile, traditional timepieces were reaching the limits of what could be mechanically measured, in astronomy and more so in sports timing, an area where electronics were again surging ahead. The atomic clock would ultimately determine fractions of a second, which were no longer measured but calculated. Would electronics sound the death knell of the Swiss watch industry? Not so sure. By working from the bottom up, tackling quartz head-on with the Swatch, Switzerland’s watch industry succeeded in reviving the mechanical watch, which became a symbol of tradition and a source of emotion.

The dream merchants

21st century

The mechanical watch’s comeback was almost as rapid and spectacular as its demise, with the result that from the early 2000s Swiss makers dominated the luxury watch market virtually unchallenged. Auctions, specialised journals and the wealth of information available online have all contributed to the mechanical watch’s return centre-stage. Particularly as brands have proved adept at spicing up ancient skills with a serving of high tech and mechanical innovation. Whether it’s a question of materials science, machining techniques, movement architecture, component assemblies or complications, watchmakers are no longer alone at the helm. Engineers are swelling the ranks of manufacturers’ R&D divisions, while designers are putting their stamp on brands’ creative studios. A watch is now the result of a holistic approach, no longer the sole preserve of legacy brands. Watchmaking is attracting fashion’s famous names alongside a “new wave” of independent makers doing extraordinary things with precision mechanisms, destined essentially for a coterie of collectors. But a watch is more than a complex assembly of miniature parts; it is also an object of beauty which has ushered in a new golden age for the decorative arts. Today, beautiful, well-made watches are everywhere, covering the entire spectrum of products and more desirable than ever. They are the stuff of dreams.

To discover more about the history of watchmaking, browse our interactive timeline here.