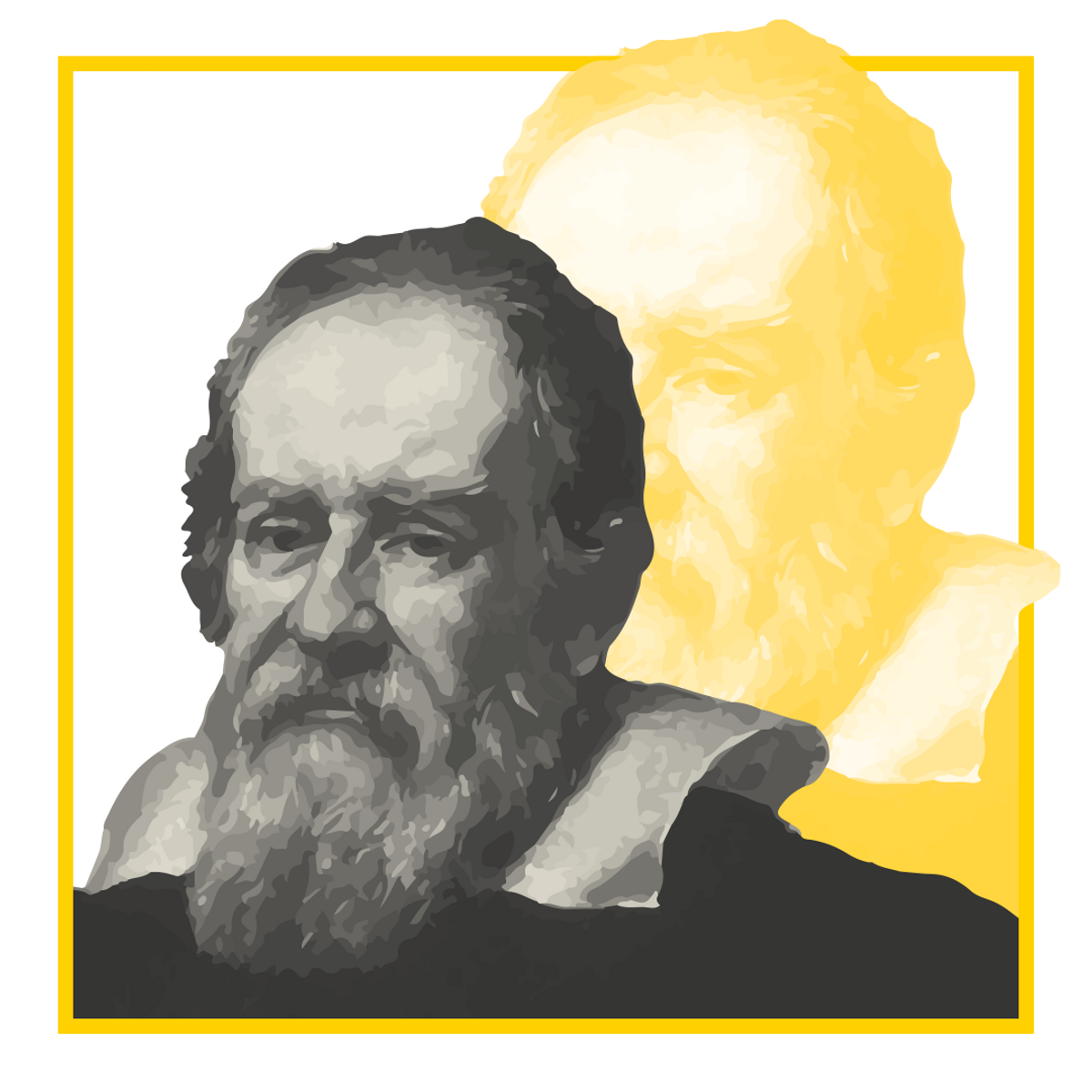

For centuries, in his infinite modesty, Man imagined himself to be the centre of the universe, convinced that Earth remained stationary and all else revolved around it. Had not the most eminent scholars, Aristotle and Ptolemy among them, formed models to prove this, just as they had calculated the distance between Earth, the two “luminaries” that are the Sun and the Moon, and the five planets - Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn - which are visible to the naked eye. With the notable exception of Aristarchus of Samos (third century BCE), ancient cosmologies were exclusively geocentric. The Church was an ardent supporter of this theory, pointing to Holy Scripture which placed Earth at the centre of the universe: Psalm 93 tells us that “the world is established; it cannot be moved.” Few opposed this dogma, all too aware of the fate the Inquisition reserved for anyone who challenged the Church’s view. The Italian philosopher Giordano Bruno, who was burned as a heretic in 1600, paid the price.

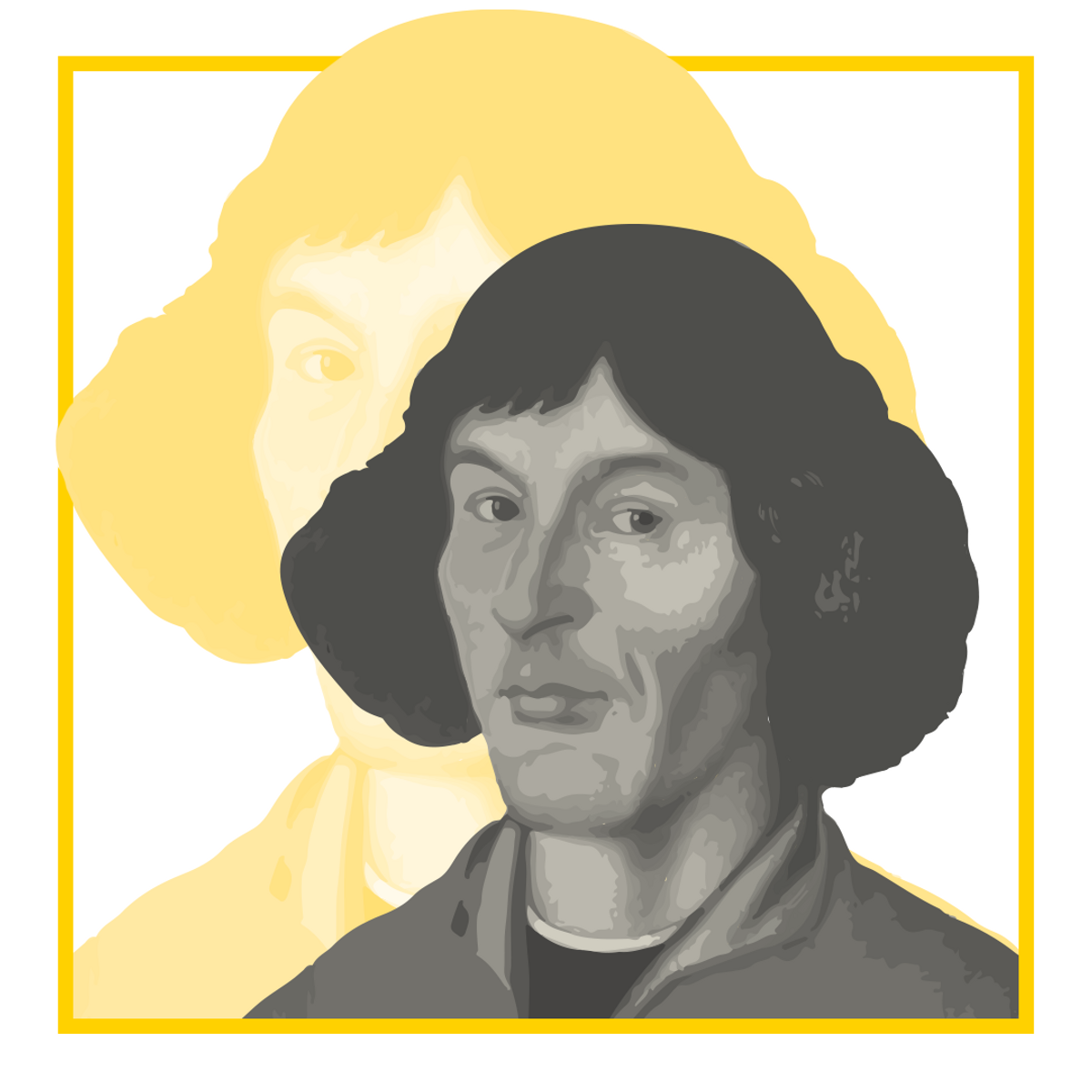

A true Renaissance man, Nicolaus Copernicus had his own ideas on the matter. A scholar in the widest sense, he read humanities at the University of Krakow in his native Poland before turning his mind to medicine, mathematics and, importantly, astronomy, which he studied in Bologna under Domenico Maria Novara. Returning to Poland, his duties as canon and administrator for the diocese of Frombork left him time to continue his astronomical studies from the town’s observatory. It was here that he conceived of his heliocentric theory, whereby Earth rotates around its axis with the Moon as its satellite, and all the planets orbit the Sun. He expounded his theories in two major works though, nothing if not cautious, he delayed publication such that the first appeared only in the nineteenth century while the second, which he completed in 1530, was published 13 years later on the day of his death. Copernicus’s theories were to be read in secret, for fear of ending up in one of the Holy Office’s cells.