Sustainability: a drop in the ocean?. Sustainability: a drop in the ocean?. Sustainability: a drop in the ocean?. Sustainability: a drop in the ocean?. Sustainability: a drop in the ocean?

Sustainability: a drop in the ocean?. Sustainability: a drop in the ocean?. Sustainability: a drop in the ocean?. Sustainability: a drop in the ocean?

10 February 2022

Sustainability: a drop in the ocean?

Forum, Sustainability

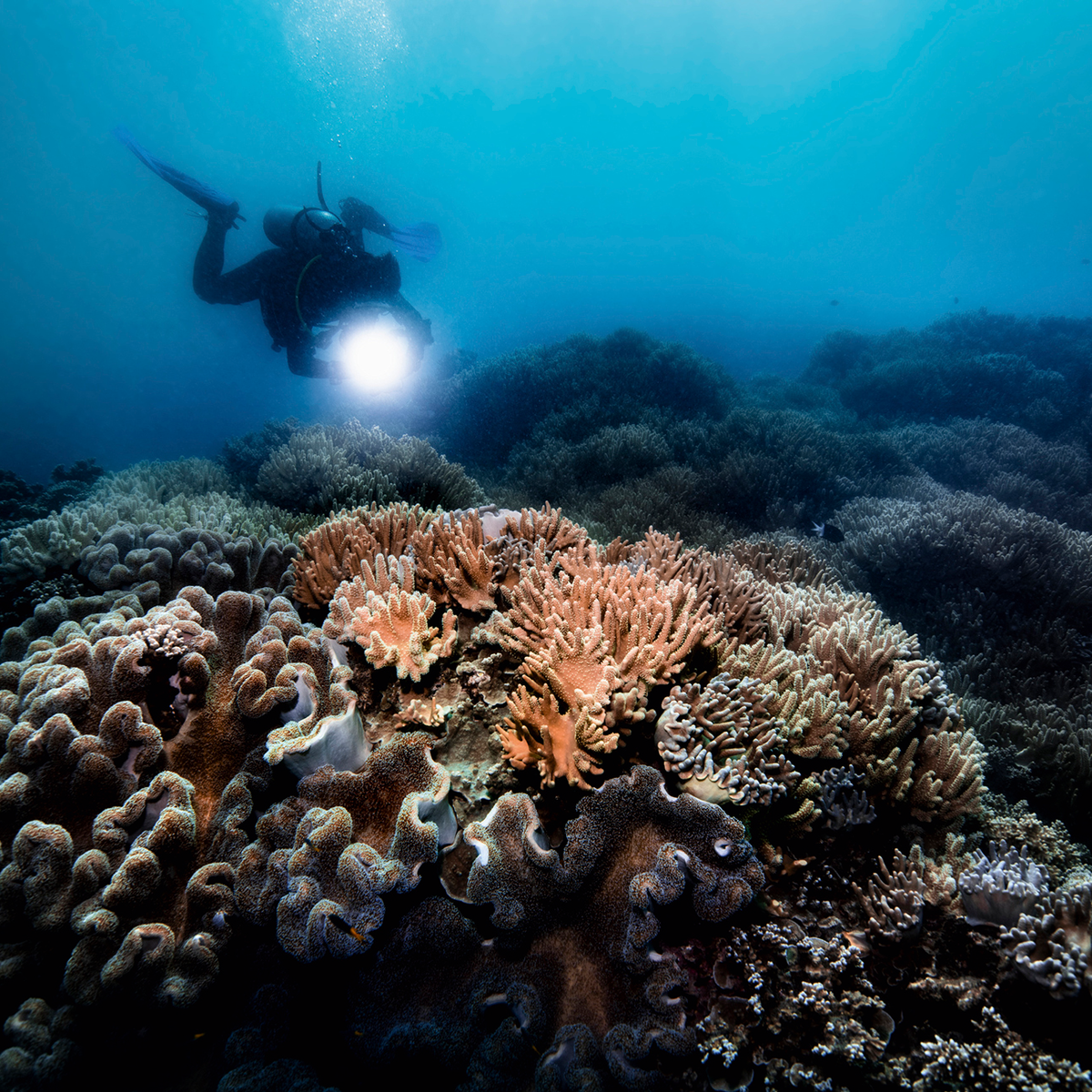

The One Ocean Summit in Brest aims to mobilise the international community to take tangible action to save the ocean. Yet another emergency for the stricken planet. Part one: taking stock.

Swimming through plastic is never a good look, and brands eager to convince us that a dive watch has qualities beyond water-resistance - qualities that make it perfectly suited to an active urban lifestyle - are doing themselves no favours by turning a blind eye to the pitiful state of the ocean. Like the rest of the environment struggling to overcome the damage inflicted by human activity, the ocean is on red alert. This is the message behind the One Ocean Summit taking place in Brest, on the west coast of Brittany, this February 9 to 11 and attended by 400 experts, scientists, heads of state and representatives of civil society and NGOs. It marks the beginning of the second year of the United Nations Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development “to support efforts to reverse the cycle of decline in ocean health and gather ocean stakeholders worldwide behind a common framework.”

The ocean in distress

Beyond well-intentioned declarations and grand concepts, the time has come for action rather than words. The ocean is the planet’s lungs, capturing as much as 30% of anthropogenic carbon emissions while phytoplankton produces 50% of the oxygen we breathe. It plays a role in the global economy: 12% of the world’s population derive their income from fishing and fish-farming. The tourism industry is to a large extent dependent on clean oceans. Maritime transport is a backbone of global trade. And yet the health of the ocean is clearly under threat, as indicated in a recent report by the Fondation de la Mer and Boston Consulting Group.

Because of mean sea level rise, estimated at between 20 centimetres and one metre by 2100, a growing number of areas will be exposed to flooding, which can be the result of recurrent tide-related factors or a consequence of extreme events. These areas will become uninhabitable, forcing mass migration. The disappearance of seagrass meadows, which are essential for carbon sequestration and as habitats for numerous fish species, is also a cause for concern, as is the destruction of the coral reefs that form a vital barrier against coastal erosion as well as being a food source. Mangrove forests have a greater ability than tropical forests to store carbon and are disappearing at a faster rate. Over the past fifty years, the planet has lost half its fish and cetacean populations.

A liberal vision of ecology

As reported by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), human activity is almost entirely to blame for the ocean’s woes. The list begins with climate change and greenhouse gases, which cause ocean warming and acidification, and continues with coastal construction and urbanisation, overfishing, proliferation of exotic invasive species and, of course, pollution. Each year, 8 million tonnes of plastic enter the ocean. Stretching from Hawaii to California, the so-called “seventh continent” is an expanse of plastic waste that extends over 1.6 million square kilometres: an area three times the size of France.

Catherine Le Gall is a journalist and author, based in Brittany. She believes the “blue economy” model for sustainable use of ocean resources is inherently contradictory. In her latest book, L’imposture océanique (published in French), she argues that the major industrial players have put forward a liberal vision of ecology based on a lack of binding measures and the absence of government regulations, and which relies on market mechanisms to protect nature. In an interview with French sustainable development website iD4D, she describes these principles as having become so widely accepted, they now shape climate policy decisions. They have, she says, permeated every level of society through lobbies, charitable foundations and the financing of powerful NGOs which, in turn, promote an economic approach to ecology. Sustainable development, like the blue economy, defend a market-driven ecology that takes a utilitarian view of nature. According to Le Gall, this explains how carbon emission trading has become one of the main tools of international climate policy.

Financialisation of nature

The next step is the monetisation and, ultimately, financialisation of nature. Again according to Le Gall, this would have the effect of giving private investors responsibility for the protection of nature. Which brings us to the question of water: a valuable commodity as we are reminded every March 22 when World Water Day raises awareness of the 2.2 billion people who live without access to safe water. At end 2020, the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) launched the first ever water futures, based on the Nasdaq Veles California Water Index which sets a weekly benchmark spot price of water rights in California, based on transaction prices in the state’s five largest and most actively traded water markets. Plans for the contract were announced in September, as wildfires fuelled by climate change raged across California. The official line at CME Group is that the futures “provides agricultural, commercial and municipal water users with greater transparency, price discovery and risk transfer, all of which can help to more efficiently align supply and demand of this vital resource.”

At this stage, we can only observe the situation in countries such as Australia, where water distribution is managed by the government and by financial markets. Water allocations are calculated per consumer based on needs, existing water reserves and rain forecasts. Farmers, municipalities and industry can trade potential excess. Alarm bells were sounded when small-scale farmers were driven to bankruptcy, as speculation pushed water prices so high they found themselves paying as much for water as they were earning from the milk they produced. Meanwhile, certain environmental groups have taken advantage of this monetisation to buy up allocations and return this water to nature.

Catherine Le Gall is among those who consider nature to be a common resource that should be protected by national and international policies, not private interests. She warns against the monetisation of nature, “divided into pieces, into financial assets to be sold with the promise of a return on investment.” By putting a price on nature, we risk seeing private capital take control of natural areas to the detriment of the local communities whose livelihood depends on them. “At no point do the financial markets provide a response to overfishing, pollution or greenhouse gas emissions,” says Le Gall. Food for thought for the One Ocean Summit.